Frequently asked questions about three of the most common knee conditions

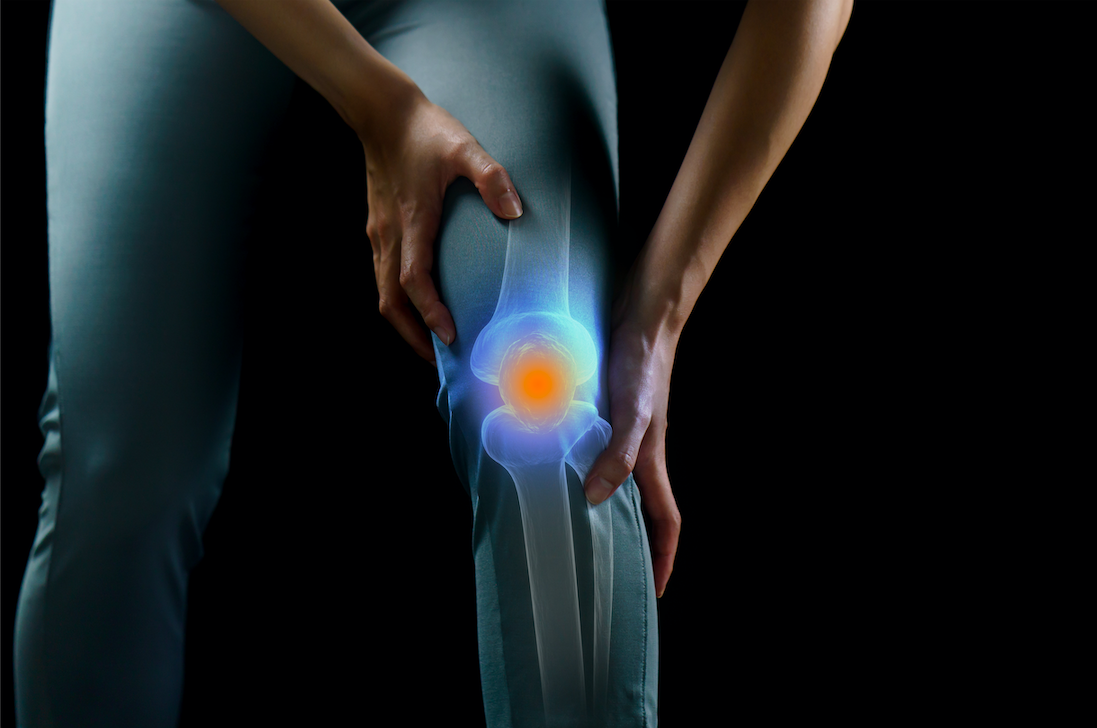

The knee is the largest and one of the most complex joints in the body. It primarily joins the thighbone (femur) to the shinbone (tibia), but also includes the kneecap (patella) and fibula in the lower leg. These bones and the muscles that surround them are connected through a series of ligaments, tendons, and cartilage (menisci) which collectively stabilize the knee and allow it to bend, twist, and rotate.

The knee also acts as a shock absorber that takes on many of the forces from the upper body to the lower body, while allowing the leg to bend back and forth with minimal side–to–side motion.

The knee's design makes it extremely durable and capable of withstanding significant loads during everyday activities and physical performance, but like every other body part, it has limits. When the knee is pushed too far–either through a traumatic injury or from gradual, sustained damage over time–it can result in a number of painful conditions.

Knee pain ranks behind just back pain as the second most common condition affecting the muscles and bones, and it's the single greatest cause of disability in individuals who are 65 and older.

There are numerous conditions that can cause knee pain, and below, we answer some frequently asked questions about three of the most common knee–related conditions:

Patellofemoral Pain

Q: What causes patellofemoral pain?

A: Patellofemoral pain syndrome, or runner's knee, is an umbrella term for any type of pain involving the patellofemoral joint (which is the joint between the kneecap [the patella] and the femur) or the area directly surrounding it. It accounts for about 20–25% of all reported knee pain and most commonly affects adolescents and young adults.

Runner's knee is an overuse injury that typically develops when the knee is overworked from excessive or repetitive movements, especially when athletes suddenly increase their activity levels. Excessive friction and stress on the patellofemoral joint and surrounding soft tissues can lead to irritation and inflammation within the joint. Poor joint alignment and weak thigh muscles may also contribute.

Q: Where does it usually hurt?

A: The most common symptom of runner's knee is pain around the front of the knee or along the edges of the patella, which frequently occurs when walking up or down stairs or hills, after long periods of activity or sitting, or after standing or walking on uneven surfaces.

Q: How can a physical therapist help?

A: Patients with patellofemoral pain may benefit from physical therapy, which is a natural, noninvasive intervention derived from a thorough evaluation of the knee and the joints above and below. Physical therapists treating runner's knee will design a program that typically includes education about the condition, stretching and strengthening exercises–with a strong focus on the hip muscles, the quadriceps, and the hamstring muscles of the thigh–sport–specific training for athletes, and possibly the use of taping or bracing and/or a foot orthotic device to help maintain the knee in an ideal position during movement.

Meniscus Tears

Q: What causes a meniscus tear?

A: The meniscus is a tough, rubbery, C–shaped piece of cartilage that rests between the tibia and femur in the knee. Each knee has two menisci (plural of meniscus), with one on the inner and one on the outer side of the knee, and both absorb shock and stabilize the knee. Meniscus tears most commonly occur from twisting or turning too quickly on a bent knee, often when the foot is planted on the ground. But older adults can experience degenerative meniscus tears, in which the meniscus has weakened and worn thin over time, and can then tear from minor trauma.

Q: How can a physical therapist help?

A: Many patients with meniscus tears can be effectively treated without surgery through a physical therapy treatment program, which will typically include manual (hands–on) therapy, strengthening exercises, icing and other pain–relieving modalities, and possibly the use of an assistive device like a cane or crutches. If you decide to have surgery–which may be recommended for severe tears in athletes and active individuals–physical therapy can help you prepare for the procedure and recover afterwards.

Q: Do I need an MRI?

A: This depends on several factors, including the severity and duration of your symptoms. Before an MRI is performed, it makes good sense to seek out the care of a physical therapist. Quite often physical therapy is all you need. While MRIs are not needed for the vast majority of mild cases, doctors may recommend having an MRI if your symptoms are moderate or severe; however, it's important to understand that this is not always necessary, and the choice is ultimately up to you. Conservative, cost–effective, natural care is what should be done first. Scientific research suggests that you should try physical therapy before having any expensive tests. If physical therapy is unsuccessful, you'll be stronger, more flexible, and better prepared for an MRI and surgery if need be. Do know that having an MRI generally increases the chances of undergoing surgery, which has been found to raise the risk for osteoarthritis in the future.

Knee Osteoarthritis

Q: What causes knee osteoarthritis?

A: Knee osteoarthritis is a disorder that involves the cartilage in a knee joint. In a normal knee, the ends of each bone are covered by cartilage, a smooth, very slippery substance that protects the bones from one another and absorbs shock during impact. In knee osteoarthritis, this cartilage becomes stiff and loses its elasticity, which makes it more vulnerable to damage. Cartilage may begin to wear away over time, which greatly reduces its ability to absorb shock and increases the chances that bones will touch one another.

Q: Where does it usually hurt?

A: Knee osteoarthritis typically leads to pain within and around the knee that tends to get worse with activities like walking, ascending/descending stairs, or prolonged sitting/standing. Other symptoms include swelling, tenderness, stiffness, and a popping, cracking, crunching sensation.

Q: Do I need an X–ray or MRI?

A: An X–ray of a knee with osteoarthritis can show a narrowing of the space between bones due to the loss of cartilage. MRIs provide much greater detail of the knee and will reveal specific changes in bones and soft tissue that may be related to knee osteoarthritis. However, these imaging tests are not often needed, and could lead to unnecessary interventions like surgery that may not alleviate the pain. This is due in part to the fact that although most individuals over 50 will have signs of knee osteoarthritis on imaging, many will not experience any symptoms. Even though an x–ray may show severe signs of cartilage loss, these findings do not mean you won't be successful with physical therapy and therapeutic exercise. Scientists have concluded that it's important for patients to try physical therapy/therapeutic exercise, rather than simply looking at an image and deciding against physical therapy treatment. In other words, no matter how bad the x–ray or MRI may look, physical therapy often helps.

Q: How can a physical therapist help?

Physical therapy is strongly recommended as an initial intervention for all cases of knee osteoarthritis. Although no treatment can slow or stop the loss of cartilage, a physical therapist can help to reduce your pain levels and preserve your knee function through movement–based strategies like stretching and strengthening exercises, hands–on therapy, bracing, and recommendations for activity modifications.